Shoreline Naturalization

For us, waterfront properties are among the most beautiful places to live. For wildlife, shorelines are an integral part of their lives. A shoreline rich in vegetation has so many benefits, not the least of which are minimal maintenance, cost-effectiveness, and a healthy lake.

Photo: Courtesy Rideau Valley Conservation Authority

Shorelines are some of the most ecologically productive places on Earth; the first 10-15 metres of land that surrounds lakes and rivers is responsible for 90% of lake life which are born, raised, and fed in these areas. Healthy shorelines help filter pollutants, protect against erosion, and provide habitat for fish and other wildlife.

BENEFITS OF A NATURAL SHORELINE

HOW TO NATURALIZE YOUR SHORELINE

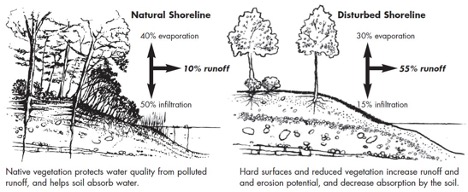

Increased development and the creation of new lots along shorelines poses risks to these sensitive areas. With the loss of buffer vegetation between lake and land, water quality, wildlife habitat, and safe swimming areas are compromised. Whether you live on a lake or river within the Lakehead Watershed, naturalizing your shoreline can go a long way!

Participate in the Superior Stewards Shoreline Protection Program

The Shoreline Protection Program is a shoreline and streambank naturalization program available to waterfront and riverside property owners within the Lakehead Watershed. Qualified applicants will receive up to 100 native plants to revegetate the water’s edge in their backyard. Click here to learn more!

How to Naturalize Your Shoreline

To help you assess the quality of your shoreline and determine your next steps, consider how many healthy shoreline attributes you can check off from the checklist below:

- There is an unmown strip of natural vegetation 10 metres wide along the length of the shoreline.

- There is a variety of vegetation near the waterfront including trees, shrubs, grasses and wildflowers.

- There is a variety of natural materials in the shallow waters offshore (rocks, gravel, woody debris, aquatic plants).

- No known contaminants are used near the shoreline (gasoline, cleaning products, pesticides).

- The shoreline is not a constructed retaining wall.

- Buildings and septic beds are set back at least 30 metres from the shoreline.

- Septic tanks are pumped regularly.

- There is no evidence of serious erosion along the shoreline.

- On sloped shorelines, paths to the water are angled across the slope to prevent erosion.

- The shoreline is dominated by plants native to the region.

- There are no invasive plants to disrupt native vegetation.

- If the shoreline has a dock, it is floating, cantilever or post construction (to allow free passage of water and wildlife).

Follow this quick five step guide to help you begin thinking about planting a natural shoreline. Refer to the comprehensive How to Naturalize Your Shoreline guide.

- Assess the current conditions of your property and envisage what a shoreline buffer might look like in your backyard. Consider access to the water, recreational activities, and views of the lake.

- Take note of any existing trees, shrubs or wildflowers. Think about the layout of your vegetative buffer, considering areas of shade and full sun, whether the site is dry or wet or a mixture of both. Determine your soil type: grab a handful of soil and rub it between your fingers, observing coarseness or smoothness. Sand grains are large and feel coarse; silt is medium thickness but feels smooth or floury; clay is fine and feels sticky; while loam is a combination of one or more of the above and generally contains a high content of organic matter.

- To find plants suitable for your property refer to the Native Plants of Northwestern Ontario factsheet, Ontario Native Shoreline Plants, or the National Native Plant Encyclopedia.

- Contact local nurseries to find the native plants you would like to use. Check out our Native Plant Supplier List.

- Once you have a plan and plants for your shoreline, study the planting specifications to determine the best time and location to plant the species. Once planted, water your plants well for the first season of growth to ensure they establish well in their new homes.

Note: If your project involves the importation or removal of fill and/or site grading and/or the building of any structures, a permit under Ontario Regulation 41/24 from the LRCA may be required.

Most Common Shoreline Plants

Experts at Watersheds Canada have compiled a list of the most common shoreline environments and the plants that work best for each. Here is an adapted version specific to Northwestern Ontario:

- Sandy, dry soil: Bush Honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera), Common or Creeping Juniper (Juniperus communis or Juniperus horizontalis), Smooth Wild Rose (Rosa blanda), Canadian Serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis), White Pine (Pinus strobus), Snowberry (Gaultheria hispidula)

- Sandy, wet soil: Willows (pussy willow, black willow, shrubby willow, sandbar willow), Canadian Gooseberry (Ribes oxyacanthoides), Swamp Rose (Rosa palustris), Red Osier Dogwood (Cornus sericea), Showy Mountain-Ash (Sorbus decora), Speckled Alder (Alnus incana), Sweet Gale (Myrica gale), Tamarack (Larix laricina), Bunchberry (Cornus canadensis)

- Clay, moist, wet soil: Common Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis), Round-Leaved Dogwood (Cornus rugosa), Highbush Cranberry (Viburnum trilobum), White Meadowsweet (Spiraea alba)

- Clay, dry soil: Smooth Wild Rose (Rosa blanda), Saskatoon Serviceberry (Almelanchier alnifolia), Snowberry (Gaultheria hispidula), Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum), Red-Berried Elder (Sambucus racemosa)

- Loamy, moist, wet soil: Highbush Cranberry (Viburnum trilobum), Sweet Gale (Myrica gale), White Meadowsweet (Spiraea alba), Prickly Wild Rose (Rosa acicularis), Red Osier Dogwood (Cornus sericea), Common Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis), Willows (Salix spp.)

- Loamy, dry soil: Bush Honeysuckle (Diervilla lonicera), Smooth Wild Rose (Rosa blanda), Canadian Serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis), Saskatoon Serviceberry (Almelanchier alnifolia), Snowberry (Gaultheria hispidula)

Photo: Common Bumblebee visiting a Prickly Wild Rose

Maintaining Your Natural Shoreline

As your buffer grows, water trees and shrubs early or late in the day at the base of their main stem. This will help conserve water by allowing the water to be absorbed by the plant faster than it is evaporated by the sun. Water in the springtime and during periods of drought throughout the summer months for the first 1-3 years as the plants establish.

Mulch (wood chips, leaf mould, hemp, compost) can be used around the base of shrubs or water-loving plants to help retain water; however, it’s a good idea to leave some of your buffer without mulch, as exposed soil and leaf matter are important habitats for many native bees and insects. Pruning can be done in moderation in late fall/early winter. Best practices suggest leaving 25% of dead branches and canes for insect habitat and soil health.